Scalia: The reasonable and the absurd. Part 2: A reduction to stone-throwing

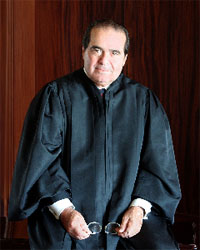

The depth of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s discomfort for things gay became apparent in 1996, ten years after he joined the court.

He had voted against the interests of gays before—allowing the U.S. Olympic Committee to bar Gay Games from calling itself Gay Olympics and allowing the organizers of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Boston to exclude an openly gay contingent.

But in 1996, he led the dissent against the 6 to 3 majority opinion in Romer v. Evans. The majority had struck down Colorado’s Amendment 2, that had barred any political subdivision in the state from prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. The majority said Amendment 2 had been driven by “animus,” not a legitimate governmental interest.

Scalia said Amendment 2 was but a “modest attempt by seemingly tolerant Coloradans to preserve traditional sexual mores against the efforts of a politically powerful minority to revise those mores through use of the laws.” It’s the sort of sentence one could imagine him cutting and pasting into an opinion defending California’s Proposition 8, banning marriage for same-sex couples.

That’s not what marked him as hostile to gays. What marked him as anti-gay was his vigorous complaint that the majority in Romer was “pronouncing that ‘animosity’ toward homosexuality is evil.”

“I vigorously dissent,” wrote Scalia.

He said he thought one could consider “certain conduct reprehensible–murder, for example, or polygamy, or cruelty to animals–and could exhibit even ‘animus’ toward such conduct. Surely that is the only sort of ‘animus’ at issue here: moral disapproval of homosexual conduct….”

In 2003, Scalia led the dissent again, this time from the 6 to 3 majority in Lawrence v. Texas. The majority decision struck down state laws banning intimate relations between persons of the same gender. But Scalia said the Texas law, which made it a felony for two people of the same sex to engage in sexual relations, simply sought “to further the belief of its citizens that certain forms of sexual behavior are ‘immoral and unacceptable’.” He took the opportunity to list the other forms of behavior that laws banned as “fornication, bigamy, adultery, adult incest, bestiality, and obscenity.”

Scalia’s comparison of consensual sexual relations between two adults of the same gender to hurtful acts such as murder, adultery, incest, and bestiality has struck many as going beyond the realm of judicial analysis and into realm of political stone throwing. It was a lasting mark on his reputation with regards to gay people and it’s what prompted a openly gay first-year student, Duncan Hosie, to ask at a Princeton University forum December 10, 2012: “Do you think it’s necessary to draw these comparisons, to use this specific language, to make the point that the Constitution doesn’t protect gay rights?”

Scalia probably experienced a flashback at that moment. In 2005, he and many others were aghast when a student at a New York University forum asked the justice, “Do you sodomize your wife?”

Both the student at NYU and the student at Princeton were challenging Scalia to explain his staunch opposition to equal rights for gays. In 2005 at NYU, various media reports indicated Scalia met the questioner with a cold stare and told him his question was unworthy of response. Seven years later at Princeton, and responding to a notably more respectful query, Scalia responded this way:

“I don’t think it’s necessary, but I think it’s effective. It’s a type of argument that I thought you would have known, which is called a reduction to the absurd. And to say that, if we cannot have moral feelings against homosexuality, can we have it against murder, can we have it against these other things? Of course, we can. I don’t apologize for the things I raised. I’m not comparing homosexuality to murder. I’m comparing the principle that a society may not adopt moral sanctions, moral views, against certain conduct — I’m comparing that with respect to murder and that with respect to homosexuality.”

So, Scalia says he compares homosexuality to murder because he believes that an extreme comparison is an effective way to convey his point. And, he doesn’t apologize for the slap of offense it conveys against gay people.

Almost every one of the ten attorneys and legal experts consulted for this report believes Scalia makes such offensive comparisons because he harbors personal animosity for gay people. Clearly, Scalia is aware of this perception. The closest he has come to refuting that perception was in his Romer dissent when he said, “it is our moral heritage that one should not hate any human being or class of human beings.” And, in Lawrence, he offered: “Let me be clear that I have nothing against homosexuals, or any other group, promoting their agenda through normal democratic means.”

But even these small efforts at civility were worded carefully enough that they conveyed nothing about what was in the justice’s own heart. They were about “our moral heritage” and the right of “homosexuals” to use “normal democratic means.”

“Social perceptions of sexual and other morality change over time, and every group has the right to persuade its fellow citizens that its view of such matters is the best,” he wrote. “…. But persuading one’s fellow citizens is one thing, and imposing one’s views in absence of democratic majority will is something else.”

Many supporters of marriage equality would argue, of course, that they are not attempting to “impose their view;” they’re attempting to exercise their right to equal protection guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution to every American.

And equal protection is the legal argument at the center of both the Proposition 8 and Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) cases this session. In these cases, defenders of the California ban on same-sex marriage and the federal law denying recognition to the marriages of same-sex couples will have to convince the Supreme Court that these laws are based in legitimate and sufficient reasons for treating gay couples differently than straight couples.

In Romer and Lawrence, Scalia said he believed the governments did justify treating gays differently. The justification, he said, was the democratic majority’s moral belief that society would be better off treating gays differently.

In 2013, the democratic majority’s belief concerning gays in general and marriage equality in particular is dramatically different than when Scalia last defended laws treating gays differently. They are also dramatically different than when the two laws were approved.

DOMA is now being applied against legitimately married same-sex couples in states where a majority of voters and/or a majority of their democratically elected representatives have said they believe it best for society to treat same-sex couples the same as heterosexual couples. And while Proposition 8 was approved by a majority of voters in California, the duly elected state officials chose not to appeal the federal district judge’s ruling that it was unconstitutional –and that decision by elected officials is part of our “normal democratic” process.

Scalia and the other justices ponder these two cases at a time when the political and moral landscapes are changing quickly on the marriage issue. In November, voters in Maine, Maryland, and Washington State voted to allow same-sex couples to marry the same as straight couples. And voters in Minnesota rejected a DOMA-like provision for their state constitution. The duly elected legislatures of four states –Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, New York—and the District of Columbia approved marriage equality. The Massachusetts legislature rejected an attempt to overturn its state Supreme Court ruling that marriage equality was mandated by the state constitution. And the Iowa legislature has declined to act on efforts to overturn its similar state Supreme Court ruling.

Today, polls indicate a majority of Americans now support equal rights for same-sex couples when it comes to marriage. An NBC/Wall Street Journal poll of 1,000 adults nationwide in early December found 51 percent favor “allowing gay and lesbian couples to enter into same-sex marriages.” Only 40 percent opposed; nine percent were unsure. When asked whether they would support a law providing for marriage equality in their own state, 55 percent said yes, 41 percent no, three percent unsure.

In fact, the most recent polls of every major independent news organization –USA Today/Gallup, CBS News, ABC/Washington Post, Associated Press/National Constitutional Center—have all found the same thing. The majority of Americans now support treating same-sex couples equally when it comes to the right to marry and the trend is evolving toward more support.

But when DOMA and Proposition 8 are before the high court this spring, most legal experts believe Scalia will vote to preserve these laws.

Any ‘morality’ originating only from religious doctrines cannot be the basis for any law, not in a secular society. Scalia has admitted that the ultimate authority, trumping the Constitution, is god. All of the details in the article add yet more proof to the obvious: Scalia allows his religious beliefs to color, to dictate at times, what he will rule in some cases. He has offered seemingly sensible arguments against this, but his arguments fail in not addressing my opening sentence. If a society deems behavior unacceptable, ‘immoral’, solely based on religious principals, then no, absolutely no way, can you pass laws based on this. Not with our Constitution.

I cannot understand how such a schmuck is allowed to stay on the bench.

Scalia is the ONLY voice of reason on the bench – he understands this is a DEMOCRACY – FOR the PEOPLE and BY the PEOPLE – not by a few judges appointed based on politics. Get it??? WHY do I vote if the “supreme court” will overturn MY vote?? HOW is THAT a DEMOCRACY??? IT isn’t